DIABETIC RETINOPATHY

WHAT IS DIABETIC RETINOPATHY?

WHAT IS DIABETIC RETINOPATHY?

Diabetic retinopathy is a disorder of major public health importance, and one of the major causes of visual loss, which cannot be corrected with glasses. The condition is due to damage to the small blood vessels that nourish the retina, the light-sensitive tissue that lines the back of the eye. There are often no symptoms in the early stages of diabetic retinopathy. Therefore, vision may not be affected until the disease becomes severe. There are four levels of diabetic retinopathy which include:

- Mild Nonproliferative Diabetic Retinopathy (Mild NPDR)–At this earliest stage, microaneurysms occur. Microaneurysms are small areas of balloon-like swelling in the retina’s blood vessels.

- Moderate Nonproliferative Diabetic Retinopathy (Moderate NPDR)– As the disease progresses, some blood vessels that nourish the retina are blocked.

- Severe Nonproliferative Diabetic Retinopathy (Severe NPDR)–Many more blood vessels are blocked, depriving several areas of the retina of blood supply. These areas of the retina send signals to the body to grow new blood vessels for nourishment.

- Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy (PDR)–At this advanced stage, the signals sent by the retina for nourishment trigger the growth of new blood vessels. These new blood vessels are abnormal and fragile. They grow along the retina and along the surface of the clear, vitreous gel that fills the inside of the eye. The vessels sometimes can bleed into the middle cavity of the eye or be accompanied by scar tissue, which can cause the retina to detach from the back wall of the eye. These complications of proliferative diabetic retinopathy, if left untreated, can cause severe vision loss.

The first two levels of this retinopathy (mild and moderate) usually are monitored by a health care provider who is skilled at diagnosis and management of the retina and can monitor for progression to more advanced levels (severe nonproliferative or proliferative retinopathy). The follow-up can be influenced by the presence or absence of macular edema (described below). While some cases of severe nonproliferative or proliferative diabetic retinopathy are followed carefully, others may receive laser treatment to the side part of the retina to reduce the chance of developing severe vision loss from blood collecting in the middle cavity of the eye or from scar tissue detaching from the back wall of the eye.

WHAT IS DIABETIC MACULAR EDEMA (DME)?

WHAT IS DIABETIC MACULAR EDEMA (DME)?

Independent of these levels of diabetic retinopathy, an additional cause of vision loss from diabetes can be macular edema. Macular edema can develop at any level of retinopathy. Macular edema is the term used for swelling in the small central part of the retina used for sharp straight-ahead vision. Sometimes, when diabetes weakens the blood vessels nourishing the retina, some of the blood vessels become leaky. Excess fluid and lipids (fatty materials) leak from the blood vessels into the retina, causing the retina to become thickened or swollen. This swelling of the central part of the retina can lead to decreased vision.

Macular edema and the various levels of diabetic retinopathy are detected during a comprehensive eye exam that includes:

- Visual Acuity Test This eye chart test measures how well you see at various distances. You can have excellent vision with no symptoms and have advancing diabetic retinopathy. Having a yearly-dilated diabetes exam is important to discovering problems BEFORE they occur and treating early to PREVENT vision loss.

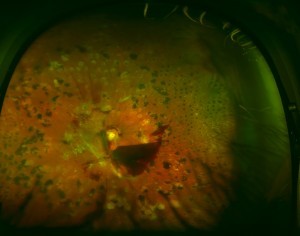

- Dilated Eye Exam Drops are placed in your eyes to widen, or dilate, the pupils. Your eye care professional uses a special magnifying lens to examine your retina and optic nerve for signs of damage and other eye problems. After the exam, your close-up vision may remain blurred for several hours. If you have not been dilated, then you have not had a complete diabetic evaluation to check for retinopathy.

- Tonometry An instrument measures the pressure inside the eye. Numbing drops may be applied to your eye for this test. It helps screen for early glaucoma changes.

HOW IS DIABETIC MACULAR EDEMA (DME) TREATED?

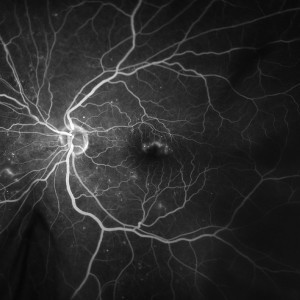

If your eye care professional believes you need treatment for macular edema, he or she may suggest simple pictures of the back of the eye, an optical coherence tomogram (OCT) or a fluorescein angiogram or any combination of the above. An OCT measures the thickness of the center of the retina and can detect abnormal features of the retina not readily apparent by other examinations or images. In fluorescein angiography, a special dye (not iodine) is injected into your arm or hand. This does not affect your kidneys like a CAT scan dye can because it does not contain iodine. Pictures (not x-rays) are taken as the dye passes through the blood vessels in your retina. The test allows your eye care professional to identify leaking blood vessels and may facilitate treatment.

Until recently, laser photocoagulation treatment was the only treatment proven to be beneficial in large trials for diabetic macular edema with reasonably long-term follow-up. When treating your eye with laser photocoagulation, your doctor places from a few to up to several hundred small laser burns in the areas of retinal leakage surrounding the macula. The laser beam creates tiny scars in the retina, helping to reduce the swelling. Laser treatment has been shown to reduce the chance that more vision will be lost by about half (50%). In addition, about 30% with decreased vision from macular edema will improve in vision by a substantial amount, although about 15% with decreased vision from macular edema will continue to deteriorate in vision by a substantial amount despite laser. It is important to identify and treat patients early in the disease because the laser treatment does not cure diabetic retinopathy or prevent future vision loss.

Until recently, laser photocoagulation treatment was the only treatment proven to be beneficial in large trials for diabetic macular edema with reasonably long-term follow-up. When treating your eye with laser photocoagulation, your doctor places from a few to up to several hundred small laser burns in the areas of retinal leakage surrounding the macula. The laser beam creates tiny scars in the retina, helping to reduce the swelling. Laser treatment has been shown to reduce the chance that more vision will be lost by about half (50%). In addition, about 30% with decreased vision from macular edema will improve in vision by a substantial amount, although about 15% with decreased vision from macular edema will continue to deteriorate in vision by a substantial amount despite laser. It is important to identify and treat patients early in the disease because the laser treatment does not cure diabetic retinopathy or prevent future vision loss.

Over the last several years, some patients with diabetic macular edema have been treated with an injection into the eye of a corticosteroid

(“steroid”) drug or a drug that stops the growth and leakage of blood vessels (called an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor drug or anti-VEGF drug). These drugs are injected into the vitreous of the eye. The vitreous is a jelly-like fluid that fills the middle cavity of the eye in front of the retina. In some patients, this injection decreased the macular edema and improved vision. In some patients, the injection decreases the swelling for a period of time, but the macular edema comes back. The Diabetic Retinopathy Clinical Research Network

(DRCR.net) conducted a study to find out if an injection of a steroid

(triamcinolone) or an anti-VEGF (ranibizumab) drug into the eye, with or without laser, is better than laser treatment and no drug for diabetic macular edema.

The results of this study show that ranibizumab with prompt laser (within a week) or with deferred laser (for six months or more) is better than laser alone for the treatment of DME. Eyes that were treated with ranibizumab with prompt or deferred laser had better vision and fewer of these eyes lost vision compared with the use of laser alone, without ranibizumab. Ranibizumab treatment may be required as often as every 4 weeks and laser may be applied multiple times, as often as every 16 weeks. Ranibizumab with prompt or deferred laser treatment, as applied in this study, should be considered for patients with DME and characteristics similar to the patients enrolled in this study.